PIONEERRESPOND

Frederick TYLER ("Fred")1873 - 1966

| |

| aka | Fred Tyler, F. Tyler |

| nationality | |

| occupation | |

| birth | 4 Feb 1873, Grantham, Manchester, Lincolnshire, ENGLAND |

| baptism | |

| death | 6 July 1966, Merton (close to Wimbledon), Greater London, ENGLAND |

| burial | |

| marriage | married on 1 Dec 1904 in Manchester, Lancashire:

Sarah Ellen ("Sally") KERSHAW Sarah Ellen ("Sally") KERSHAW b. 8 Apr 1873, Manchester |

| children |

|

PARENTS

| father | James TYLER b. .... <1835>, Denton, Lincolnshire |

| mother | Fanny ....... b. .... <1837>, Droitwich, Worcestershire |

| marriage | they got married on .. |

| children |

|

LIFE

1871 CENSUS (Grantham, Lincolnshire):

James TYLER (37y)

Fanny TYLER (35y)

- Edith TYLER (8y)

- Fanny S. TYLER (2y)

- Charles J. P. TYLER (3m)

1881 CENSUS (Portsea, Hampshire):

James TYLER (46y)

Fanny TYLER (44y)

- Edith TYLER (18y)

- Fanny S. TYLER (12y)

- Charles J. P. TYLER (10y)

- Frederick TYLER (8y)

1891 CENSUS (Ardwick, Manchester):

lives with the ROBENS family ("ROBINS" acc. ANCESTRY)

Charles J. TYLER (20y) clerk mercantile

Frederick TYLER (18y) bookkeeper

1901 CENSUS (Ardwick, South Manchester, Lancashire):

Frederick TYLER (28y) commercial clerk (lives as cousin with ROBENS family)

joined The Gramophone Company on 1 Dec 1904 (letter Dec 1907, Cairo)

1904-1 July 1906: Brussels (see letter 31 May 1906 (Muir to Fassett)

July 1906-March 1909: Egypt

1909: Moscow

1910-1917/18: Tiflis/Tbilisi (Georgia)

1919-1920: Bombay

1921-1927: Brussels

1928-1937: Paris

For more details see Tyler's autobiography (adapted by Edith Watson)

Frederick TYLER (64y)

Sarah TYLER (64y)

SS "LAFAYETTE"

dep.: 13 Sep 1937, Southampton

arr.: 21 Sep 1937, New York

his brother C. [= Charles J. P.] TYLER, Denton, Old Colwyn, North Wales, GREAT BRITAIN

via San Francisco (c/o Matson Lines Steam, San Francisco, CA)

Frederick TYLER (no age) tourist

SS "EMPRESS OF BRITAIN"

CROSS CHANNEL

dep.: .. June 1938, Cherbourg

arr.: 30 June 1938, Southampton

Home address: 22 Chiltern Court, London N.W.1

Frederick TYLER (British Consul) (66y)

+ Mrs. TYLER (no age)

SS BREMEN

CROSS CHANNEL

dep.: .. Apr 1939, Cherbourg, FRANCE

Arrival: 20 Apr 1939, Southampton, ENGLAND

Country of last residence: FRANCE

Address in UK: 22 Chiltern Court, London N.W.1

The following two incomplete typewritten manuscripts were given to me by Frederick Tyler's daughter Mrs. Edith Watson (née Tyler) of Chichester.

They consisted of:

(1) a text entitled Records in the making, apparently composed and typed out by Frederick Tyler himself (or a typewritten version of an original handwritten text).

(2) two chapters of a manuscript that is an adaptation of Tylers original article, written by his daughter, Edith Watson.

At the time Mrs. Watson also sent me one photograph of her father and one of Yousef Adem, the companys traveller in Egypt. Both pictures are reproduced on this website.

In 1994, while in England, I decided to visit Mrs. Watson at her home in Chichester, but I came too late: it turned out Mrs. Watson had died.

Her husband Malcolm J. T. Watson had died earlier and the couple had no children.

I have no idea what happened to the documents of the Tyler family...

Records in the making

by Frederick Tyler

During my association with His Masters Voice Gramophone Co. and the Columbia Graphophone Co., extending over 33 years, between 1904 and 1937, I have naturally come into touch with many celebrated artistes whose performances have been recorded and thus preserved for

posterity.

I joined the company in Brussels in 1904 and since then have served them in many countries including Egypt, Russia, India and France.

Egypt

My first contact with artistes was in Egypt during the years

1906 to 1908 when we were interested in recording the most famous of the native singers and instrumentalists whose fame, although little known to Europeans, was very high amongst their own compatriots in Egypt and Syria, and indeed through all the Arabic speaking countries.

Many of the resulting records made at that time by such singers as the late Cheikh Youssif Abdel Hai and others are still in circulation and are highly prized by lovers of Arabic music at its best. The accompaniments to their songs were played on the canoun, a many-stringed instrument similar in shape to a guitar but with metal cords and played with the canoun laid flat on a low table, thus permitting the use of both hands.

As, until recently, there was no written music, the instrumentalists were the preservers of the old melodies and composers of new. In most cases they acted as teachers and mentors to the singers to whom they were by no means inferior in reputation and worth; usually commanding fees equal or superior to the singers.

The half and quarter tones used in Eastern music make it sound more or less incomprehensible to Western ears but it has an undoubted charm which increases with familiarity.

The importance of preserving and encouraging all that is best in Arabic music was signally recognised by the late King [Fuad] who shortly before his death was instrumental in convoking a conference on Eastern music in Cairo to which was invited the pick of singers and instrumentalists from all the Arabic-speaking nations, such as Syria, Tunisia, Algeria, Morocco and many others. I was instrumental, whilst in Paris, in arranging, with the Egyptian Minister to France, for a special recording mission to attend this conference and make a collection of records which were to be preserved in the Cairo museum [14 March - 3 April 1932 held at the National Academy of Music, at 22 Malika Nzaly Street, now Ramses Street)

This conference was attended by the leading musical critics of

all the European nations and created a great deal of interest. The recording was successfully carried out and there now exists in the Egyptian archives a series of records made by all the visiting and local artists which should prove of great historical value.

Moscow

Early in 1909 I was transferred from the heat and dust of Egypt to the cold and snows of Moscow, from the exotic, semi-barbarous Eastern melodies to the plaintive, highly emotional music of the Slav.

By far the most colourful, magnetic personality I encountered in Moscow was Feodor Chaliapin, at that time approaching the summit of his phenomenal career. Not many years previously he had drifted from the banks of the Volga to Tiflis, in the Caucasus, where, to eke out a living, he had sung a few topical songs in open-air cabarets for a few roubles per performance. Here he was noticed by a member of the Tiflis Musical Academy who arranged for him to study singing. From there to performances in Opera was but a step and his wonderful voice and almost more wonderful interpretation of such roles as Boris in Boris Godunov opened the way to universal fame. It can truly be said that he has created a Boris unlike anything previously known and never likely to be equalled. His record of the Volga Boat Song with a male voice choir started a vogue and made this stirring folk song known all over the world. His very volatile temperament caused many difficulties on the operatic stage and he was not always easy to handle in the recording studios.

After the death of her father in 1966, Edith Watson, decided to re-write the manuscript of her father and began adapting it.

Mrs. Watson divided her manuscript into chapters; I was given only two chapters (5 and 6). Chapters 1, 2, 3 and 4 are missing.

Which person or institution has the complete manuscript?

CHAPTER 5

During the early summer of 1906 father was tranferred to Egypt.

Mother, again pregnant, went back to England.

The next card is one from Alexandria dated 23rd July 1906 on which father had written to his brother [Charles]:

Had a letter from Sallie to-day. All goes well. She will probably be going to M/chr [=Manchester] for a short while and might like to stay with you for a day or two. Can you manage it?

Mother was at her brothers home in Draycott, Derbyshire.

She cannot have been contemplating moving about because my brother Charles Frederick was born on August 2nd [1906].

It seems that Uncle John, before writing decided to wire the important news to father at his office in Alexandria. Whether for economy, or just for fun, he sent the one word son and the Egyptian staff spent some time with code-books trying to sort this out.

There is a lovely photograph taken after Charles christening. It shows a group at the front door of Lauderdale. Mother and baby are flanked by the entire John and Hannah Kershaw family, all their eight children having been born by now. The oldest was John, aged 13, who was to be one of the many thousand reported as missing, presumed dead after the battle of the Somme in 1916.

But all was happiness in 1906. On October 20th father sent a card from the Rue Cherif Pacha in Alexandria:

Mr. [Kenneth] Muir is here and has arranged for my salary to be 300 per year from the first of this month and the Company will pay the difference in the cost of living etc. since July 1st, so that the cash I have borrowed from the firm will be wiped out. Am anxiously awaiting news of your departure.

Just to get mother in the mood for Egypt the card showed a group of Bicharis [Bisharis] near Assouan.

Mother and baby Charles sailed from the Manchester Ship Canal on the Ocean Prince. This was on November 17th when Charles was nearly four months old. Uncle John escorted them to the ship the evening before she sailed. It had been thought better for mother and baby to get settled in advance of the other passengers. She said that she lay in her berth listening to the sounds of loading and got up to put cotton-wool in the babys ears because of the bad language.

I think she thoroughly enjoyed the voyage in spite of bad weather in the Bay of Biscay, so bad, that no one came when she rang for a stewardess to replenish her drinking water. Mother could, I think, have been an actress. I can still see her dark eyes flashing as she recounted:

I somehow staggered to the cabin door to look for someone. The passage was awash with sea-water and I saw a figure in glistening oil-skins and called Is there no-one to help me?

Help came, and later during beautiful weather she was invited to the captains table for a meal and heard him call to a steward Is there no-one to help me?. She burst out laughing and said: Oh, it was you!

During the voyage she was befriended by two women missionary doctors (Drs. Patterson and Berry) who were on their way to Jenin in Palestine. The crew also made much of the baby boy and rigged up a small hammock for him.

All her life mother kept a religious poem which the two doctors had given her, although she was not a particularly devout woman. The church-going we all enjoyed as a family years later was the Russian Easter mass. It was impossible not to be affected by the atmosphere the expectant standing congregation holding unlit candles the lighting of candles one from another the gradual increase of light, colour and gleam the procession outside the church (a symbolic search for the body of Christ) - the dramatic throwing open of the altar gates and the announcement Christ is risen with the reply Aye, verily, He is risen and the wonderful unaccompanied singing of the choir.

It seems hard that father was not with mother for the birth of

their first child, nor did he see me until I was seven months old. It was, though, mothers wish that her children be born in England. Although she sometimes complained later about these absences on important occasions, each birth more or less coincided with a change of country, possible promotion for father and, in the case of Russia, a new language for him to master at top speed. After all, devotion to his job meant security for his family. One cant have it all ways.

When mother and young Charles arrived in Alexandria they all moved to a small house right on the edge of the desert. Mother loved this house and was, I think, sorry when they moved to Cairo which was fairly soon afterwards. While they were still in Alexandria she lost her engagement ring which was a little loose. She was dolefully telling a friend about the loss while they were standing just outside the enclosure of their courtyard. She was tracing patterns in the sand with the toe of her shoe while looking down and there was the ring. I think Alexandria became a still more magical place to her after that.

In Cairo they lived at Shareh Sabri in an apartment, I think, and then moved to the Villa Rose, Zeitun.

Fathers job must now have involved rather more than bookkeeping because he wrote: My first contact with artists was in Egypt...

While still at Shareh Sabri they had also met the Gramophone Companys roving impressario Fred Gaisberg. He took a photograph of mother and Charles, aged 7 months, mother with a horsehair fly-whisk at the ready. The three adults were all the same age, all born in 1873, and a lifelong fniendship began. So much has been written about Fred Gaisberg, this exceptional man of genius and perception, so I will only comment on the impression he made on me later. He had an amazing acceptance of and interest in people of all kinds and at once showed sympathy and understanding. No wonder he had so many friends and was such a rock of reassurance to temperamental artists. One of the photographs he took in Egypt is dated March 1907. Early in this year the Company had moved to more spacious premises at Hayes in Middlesex and. the name Typewriter was soon to be dropped. From 1908 it would be known as The Gramophone Company.

Father wrote:

In Egypt, recording was being arranged of the more famous singers and instrumentalists. These artists, although at that time little known to Europeans, were very popular throughout all the Arabic-speaking countries. Singers were accompanied on the canoun, an instrument similar to a guitar with many metal strings and plays flat on a table, permitting the use of both hands. At that time this music was not written down, so the instrumentalists were the preservers of old melodies and composers of new ones. They often acted as teachers and mentors to singers, and commanded equal fees when being recorded.

Father was not particularly musical, although he had a tuneful singing voice, and at first the half and quarter tones used in Arabic music made little sense to him. With familiarity he came under its spell and this was reinforced later when he heard similar music in South Russia.

Some time between 1945 and his death in 1966 father wrote an article and called it Records in the Making. It begins:

During my association with His Masters Voice Gramophone Co. and the Columbia Graphophone Co., extending over 33 years, between 1904 and 1937, I naturally came into touch with many celebrated artistes whose performances have been recorded and thus preserved for

posterity.

I joined the company in Brussels in 1904 and since then have served it in many countries including Egypt, Russia, India and France

Like mother, he must have run out of steam, and the article finishes with his return [to England] from Russia in 1918. I will copy extracts as they slot into the overall narrative. He continued as follows:

The importance of preserving and encouraging all that is best in Arabic music was signally recognised by the late King Fuad [1868-1936] who, shortly before his death, was instrumental in convoking a conference of Eastern music in Cairo [in 1932], to which was invited the pick of singers and instrumentalists from all the Arabic-speaking nations, such as Syria, Tunisia, Algeria, Morocco and many others. While I was in Paris in the 1930s, I arranged, with the Egyptian minister to France, for a special recording mission to attend this conference and to make a collection of records which were to be preserved in the Cairo Museum. This conference was attended by the leading music critics of all the European nations and created a great deal of interest. The recording was successfully carried out and there now exists in the Egyptian archives a series of records made by all the visiting and local artists. It should prove to be of real historical value ...

But back in 1907 there is a photograph of my parents with young Charles and Auntie Ison who helped mother while she was in Egypt. Mrs. Ison had no children of her own. She remained a lifelong friend and as an elderly widow lived near us in Wimbledon in the 1950s. She was a friendly woman with an earthy sense of humour and I liked her very much. After her husbands death she and their adopted daughter, Sheila, remained in Egypt for many years, Sheila meanwhile growing up to be beautiful and breaking many hearts en route. Auntie Ison was extremely capable and held a post as matron at the Nasria School, Rue Champollion, Cairo.

There is a 1937 Christmas card from her with a photograph of the school with the Head and Auntie Ison. The 31 boys (prep. school age) and the Head are all wearing the Egyptian fez. Auntie said she loved the boys and the only difficulty she had was in trying to persuade them not to cover their heads in bed at night. They continued to do so of course and she used to go round when they were asleep gently uncovering their noses, at least.

There are other pictures in the 1907 scrap-book - one of Charles aged about 1½ in the garden of the Villa Rose.

He is wearing a dress (standard wear for baby boys then) and a sun-helmet and is holding the spout of the garden hose, with mother in the background in charge of the tap. He soon learned to turn on the tap, though, and with luck give someone a soaking. Father called him Le petit pompier. Before this when he was well anchored in his chair on the verandah he amused himself by calling Bawtah and twirling his water drinking-bottle round. Mother said she used to rush out to save the bottle because he loved to hear it crash. She said that apart from the expense of the bottles which could only be bought at one particular Cairo chemist, the water had to be boiled and cooled.

They had a canary at that time. It was called Pretty and was much loved. The cage hung in the shade on the verandah and one day mother saw a hawk with its wings round the cage.

She ran forward and the predator flew away but two bars of the cage had been forced apart and the canary decapitated. Mother said that her feelings of grief and rage were so overpowering that she could have strangled the hawk. They never had another caged bird.

There is a photograph of the three of them, taken in February 1908. Father in a high stiff collar, mother with parasol (3 months pregnant and looking rather wan) and Charles in his dress. There is also a studio photograph of father, taken by the Atelier Horos, Cairo, father with a thick moustache twirled up at the ends.

Mother and her sister Polly must have been in touch the two sisters at opposite ends of the African continent and news must have come through of Pollys second pregnancy. The latter returned to England in time for Irenes birth in May at Lizzies home in Derbyshire.

Mother also returned to England with Charles to await my birth. This time she went to Manchester. She said it was a joy to stand at the door of her old home, letting the cooler English air penetrate every pore. She had brought back one continental custom, though, because having thrown her bed-clothes on the sunny window-sill to air she was startled to see her mother, white-faced and panting, having run up the stairs and crying out Sally - how could you - what will the neighbours say?

Mother rented a furnished house at No. 8, Milton Mount, Gorton, and here at 8 a.m. on a Sunday morning, August 9th 1908, I was born. What with the 8s and the 9s she muddled my date and from then on my birthday was celebrated on August 7th. It was only when I needed my own passport at the age of 16 that my birth certificate was scrutinised and the date re-established. Mother said Oh you were born at No. 8, [Milton Mount], and I knew it was either on the 7th or the 9th. I felt quite peculiar and ever since have looked on the 7th as almost mine. On the certificate father was still described as a book-keeper. There is an ornate baptismal card with a verse in which are the words Henceforth no evil dream befall thee ..., which have always pleased me. All these documents are copies of the originals which were left behind in Russia.

One of my cousins, Nellie, has said that she used to love coming to 8 Milton Mount because it was such a big house. It had need to be because Auntie Polly, with young Bob and Irene, aged 3 months, came to stay before they returned to Johannesburg.

Before leaving Egypt for good, father must have been moved back to Alexandria because there is a postcard from there c/o The Gramophone Company Ltd.. It is dated 26th August 1908. He wrote:

You will have heard all the news no doubt that we now have a complete assortment in our family. If the latest addition is up to the original sample well have no cause for complaint... The change to Alexandria has done me good. Am feeling very fit...

He must have stayed there until the early part of 1909 because there is a document showing that he was initiated into Freemasonry at the Albert Edward Scottish Lodge in Alexandria on February 19th of that year.

The last picture we have of Egypt was presumably taken in Alexandria because on the reverse father has written Joseph Adam, our traveller from Cairo.

CHAPTER 6 (page 19 in Edith Watsons manuscript)

Father probably left Egypt in March 1909. Before coming to join us in Manchester, he must have visited Head Office at Hayes to get instructions about proceeding to Russia.

Before we left Manchester, Fred Gaisberg must have arranged for his two sisters, Carrie and Louise, to visit us. Mother has told me that they arrived, beautifully dressed, and it was decided that they should all go to Belle Vue, an amusement park. Coming down one of the chutes on a mattress, Louise split one of her fine kid gloves. Mother said how grateful shed been to her for laughing this off and saying it was her fault for wearing such thin gloves.

We arrived in Russia on April l4th 1909. There is a coloured postcard with a general view of Moscow which father had sent home:

Hotel de Berlin, Moscow, Tuesday afternoon.

. arrived safely at 1 oclock. All well but a bit tired with the journey. Had comfortable compartment to ourelves all the way. Restaurant car, lavatories etc. on the train. Have nice room in hotel and can see a bit of the life of Moscow from the window

.

Father must at once have started learning the language. He said it took him a years hard slog, working in the evenings. He must very soon have met Edmund J. Pearse, another HMV man and an extremely clever recording engineer, who was based in St. Petersburg. He had much experience of HMV recording techniques, having worked in China with Will Gaisberg, Freds older brother, and in Italy with Fred Gaisberg himself.

Father wrote later:

Early in 1909 I was transferred from the heat and dust of Egypt to the cold and snows of Moscow, from the exotic, semi-barbarous Eastern melodies to the plaintive, highly emotional music of the Slav.

By far the most colourful, magnetic personality I encountered in Moscow was Feodor Chaliapine, at that time approaching the summit of his phenomenal career. Not many years before, he had drifted from the banks of the Volga to Tiflis, in the Caucasus, where, to eke out a living, he had, for a few roubles per performance, sung a few topical songs in open-air cabarets. Here he was noticed by a member of the Tiflis Musical Academy who arranged for him to study singing. From these lessons to opera performances was but a step and his wonderful voice and almost more wonderful interpretation of such roles as Boris in Boris Godunov opened the way to universal fame. It can truly be said that he created a Boris unlike previous singers. Also, his record of the Volga Boat Song with male voice choir started a vogue and made this stirring folk song known world-wide. His very volatile temperament caused many difficulties on the operatic stage and he was not always easy to handle in the recording studios. He wanted each record to be a master-piece and personally supervised every detail, drilling orchestra and choir until he had everything to his liking.

One evening when Chaliapine had finished recording in our Moscow studio and had received 500 roubles (about £50) on account of his fees, He invited three or four of us to accompany him to Yar, the

Alas, at this point my photocopies end.

Mrs. Edith Watson (née Tyler) died in 1993 and I do not know what happened to the Tyler material...

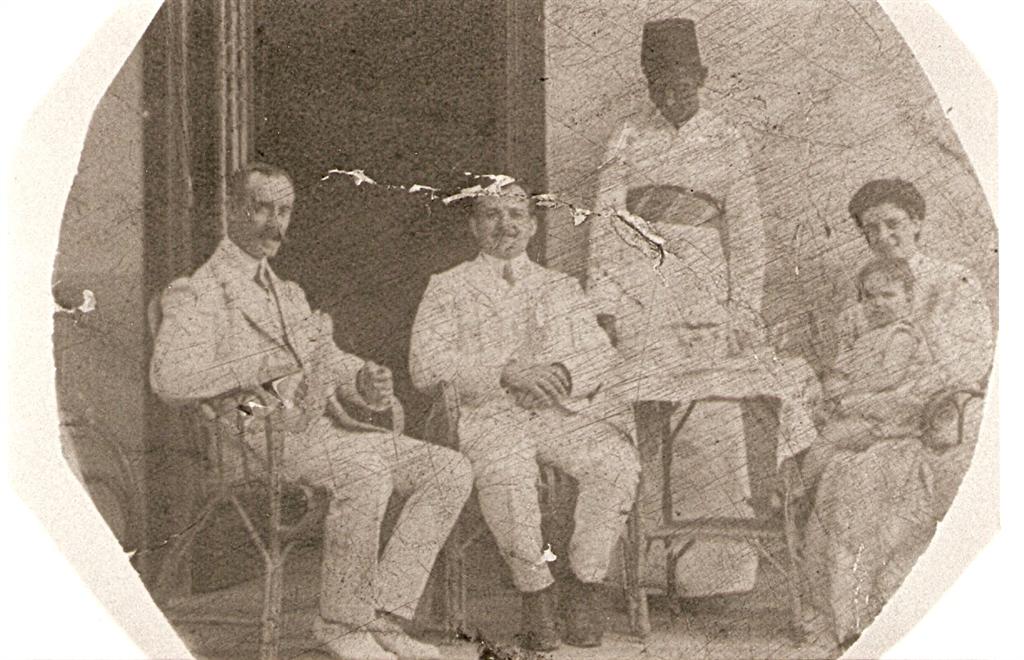

A key figure in Russia was Frederick Tyler who combined the duties there of shopkeeper, mechanic, impresario and produceras well as being British Consul there. Picture shows the imposing Gramophone Company premises in St. Petersburg. (source: Billboard of May 21, 1977). on internet

|

|

NOTES

- Cairo Congress of Arab Music (Wikipedia)

- Goulash, Wiener schnitzel and sis kebap: Premier Record by Hugo Strötbaum (in: The Lindström Project. Contributions to the history of the record industry / Beiträge zur Geschichte der Schallplattenindustrie. Vol. 4, pp. 128-145 (editors: Pekka Gronow & Christiane Hofer). Gesellschaft für Historische Tonträger, Wien 2010. ISBN 978-3-9500502-0-2

COMPANIES & LABELS

PHOTOS

|

| Frederick Tyler (on the left) and unknown family in Egypt (1906-1909) |

|

| Fred Tyler, manager of the Tiflis office of the Russian branch (in the middle) and recording engineer Edmund Pearse (1911-1914). |

THANK YOU

Edith Watson

EMI Music Archives

Will Prentice